Surprising critic of Coke

At Emory, a company bastion, the student paper has joined the chorus questioning practices in Colombia.

By CAROLINE WILBERT | Atlanta Journal-Constitution | 1/29/06

Read Original Article by Subscription

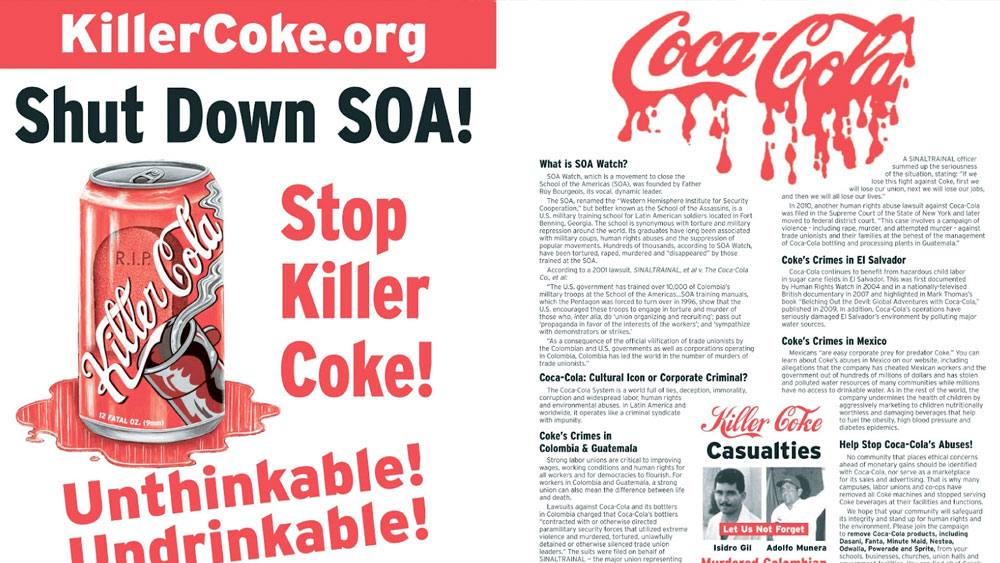

Allegations that Coke was complicit in human rights violations in Colombia have fueled student protests on campuses nationwide, sparked college newspaper editorials and prompted some schools to ban the soft drink.

So what's the big deal that yet another student newspaper ran an anti-Coke editorial this week?

Well, the latest newspaper is at Emory University.

Otherwise known as Coca-Cola University.

That's right, the school built on land donated by Coke founder Asa Candler, the school that made headlines in 1979 when Coke's legendary leader Robert Woodruff and his brother donated $105 million in Coke stock, the school with a business school named for another Coke chairman, Roberto Goizueta, the school where seniors annually toast their graduations with — you guessed it — Coca-Cola.

Geoff Pallay, the editor of The Emory Wheel and a senior, said the university so closely associated with Coke shouldn't ignore the Colombia issue.

"It does come across that Coke is ignoring it," Pallay said. "What we are trying to say is, 'Coke, that looks bad and it affects us.' "

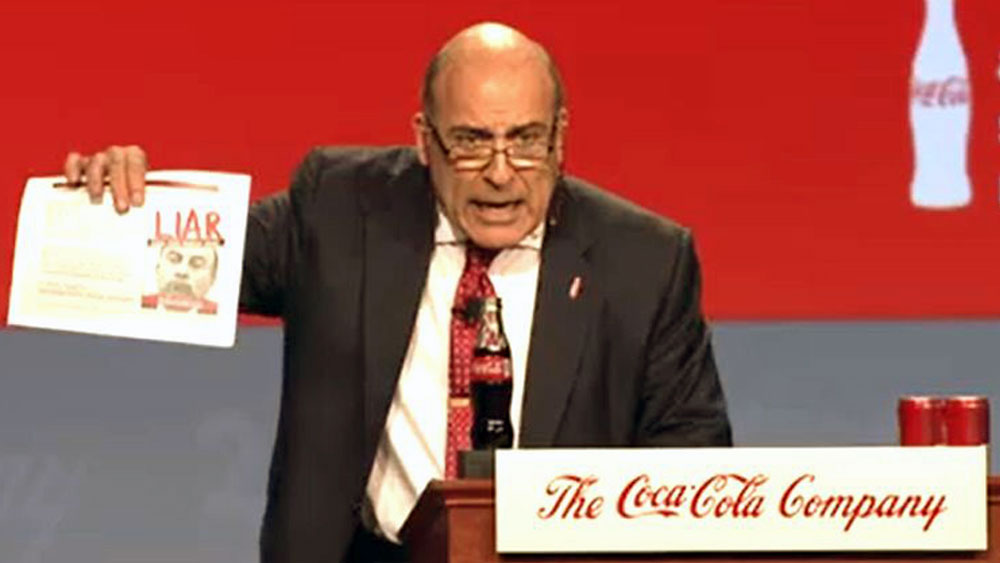

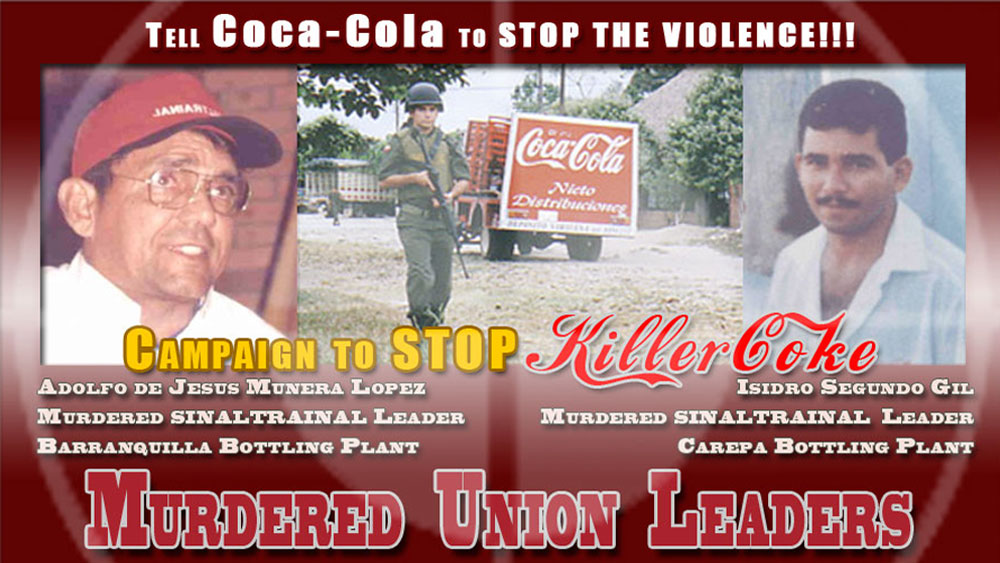

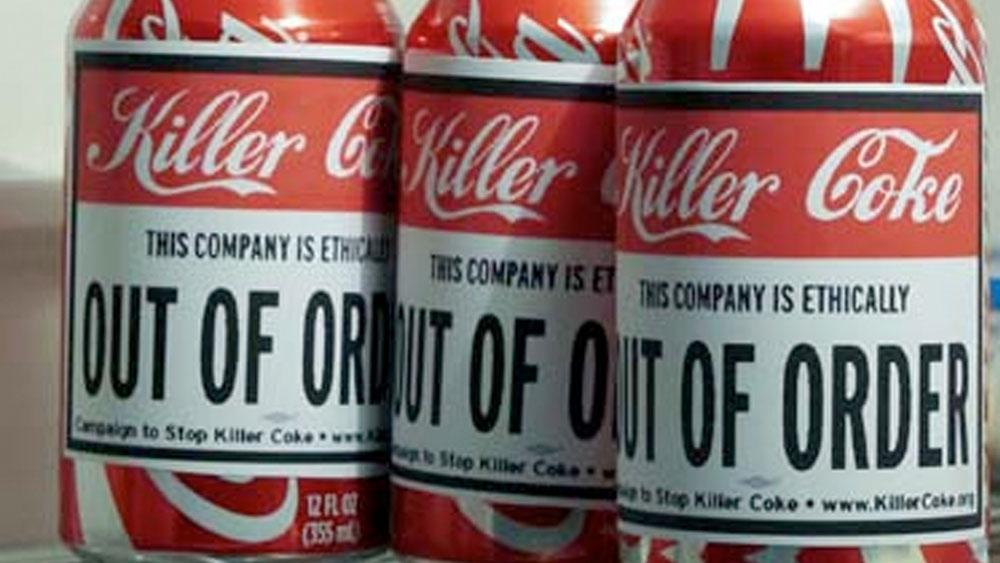

For several years, student activists across the country have claimed Coke and one of its bottlers had something to do with violence against union organizers in Colombia, including the murder of a worker in a Coke plant in 1996. The company has denied the charges, but the issue keeps getting more attention, thanks to a well-organized grass-roots organization called the Campaign to Stop Killer Coke that is led by longtime labor activist Ray Rogers.

The drumbeat got louder recently when two universities, the University of Michigan and New York University, banned Coke from their campuses. The schools want an independent investigation into what happened in Colombia.

The Wheel editorial in Tuesday's edition, tame by student newspaper standards, also called for a third-party assessment instead of a Coke prohibition.

Emory University's president, Jim Wagner, said he hasn't heard any flak from Coke about the editorial. He's glad the student journalists practiced restraint, he said.

"I am pleased to see that our students are interested in seeing due process," he said. "Certainly, if there was any wrongdoing in the past, Coke needs to be held responsible for it."

Coke was cleared of wrongdoing in an investigation that it funded.

Though Coke says it is committed to participating in an independent investigation, the sticking point is that the company doesn't want the findings to be admissible in a lawsuit filed in Miami by the International Labor Rights Fund on behalf of the Colombian workers. Coke has been dismissed from the suit, but its Colombian bottler is still involved.

"We stated last week a commitment to an impartial, independent, third-party assessment in Colombia, which would address the concerns of the Emory students," Coke spokeswoman Kari Bjorhus said. "We remain confident that the Coca-Cola system has among the best labor practices among the multinationals."

Meanwhile, on the Emory campus, the editorial hasn't caused a big stir. Some students on Friday said they hadn't read it, while others said the issue is an important one the school has to confront. Many expressed doubt that a school with such close ties to Coke would consider a ban.

Emory's $4.4 billion endowment as of June 30 was the 11th-largest in the country, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education. Though the school has diversified and doesn't hold as much Coke stock as it once did, the soft drink giant played the key role in Emory becoming a nationally recognized university.

"If we thought there was a problem with Kraft Foods, yeah, but never with Coke," said senior Laura Whigham about the possibility of a ban, while she was eating lunch at a table overlooking Coca-Cola Commons in the heart of the Emory campus. Whigham said her father works at Coke.

A campus chaplain, 32-year-old Glenn Goldsmith, said he hasn't heard too much buzz about the topic. "I seriously doubt Emory will bite the hand that feeds it," he said.

Staff researcher Nisa Asokan contributed to this article.

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.