Coca-Cola heirs sue SunTrust

By Jill Lerner | Atlanta Journal-Constitution | Issue: 6/12/05

Two heirs of a fortune in Coca-Cola stock are suing SunTrust Banks Inc., claiming SunTrust's mismanagement of their trusts cost them millions of dollars.

The lawsuit, filed May 31 in federal court in Atlanta, alleges SunTrust (NYSE: STI) refused to diversify the trusts out of The Coca-Cola Co. stock (NYSE: KO) despite repeated requests by the beneficiaries, and calls into question whether the historically close ties between two of Atlanta's business pillars are too cozy — and potentially costly — for comfort.

The dispute has other Atlanta connections. It stems from a trust created in the 1940s by Dr. H. Cliff Sauls, a prominent Atlanta physician with close ties to Coca-Cola and Piedmont Hospital. One of the plaintiffs is Thomas Shaw, son of the former director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Robert Shaw.

In the complaint against SunTrust, Shaw and his half-brother, Alexander Hitz, who are grandsons of Sauls and beneficiaries of the trusts, claim SunTrust breached its fiduciary duties, and engaged in gross neglect for its "all eggs in one basket" strategy. They allege that despite repeated requests to SunTrust to diversify their trusts out of Coca-Cola stock — which they say at one point were concentrated as high as 90 percent in the beverage company's common stock — SunTrust would not heed their advice because of conflicts of interest and the bank's own stake in Coca-Cola.

Between 1998 and May, the beneficiaries say, the value of the trusts declined from about $14 million to $6 million, and as a result their disbursements from the trusts also declined.

The plaintiffs claim they lost at least $15 million, which includes the $8 million decline in market value as well as the value of lost income and investment opportunities.

As of Feb. 16, SunTrust "beneficially" owned itself or on behalf of others 116 million shares of Coca-Cola stock, or 4.81 percent of Coke's outstanding shares, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing. (SunTrust's predecessor, Trust Co., received a large number of Coca-Cola shares as a result of helping to take Coca-Cola public in 1919. As the company's bank, Trust Co. also administered many individual trust funds filled with shares of the company.)

Of these shares, the bank as of Dec. 31, owned in its own name 48.3 million shares with a market value at that time of $2 billion. In 2004, the value of SunTrust's own Coca-Cola shares fell in value by $445.6 million, according to the bank's annual report filed with the SEC.

In 2004, the bank earned dividends from that Coca-Cola stock of $43 million, according to the annual report.

Additionally, executives of both companies sit on each other's boards.

Concerns about SunTrust's close ties to Coca-Cola are nothing new, according to author and Coca-Cola expert Frederick Allen. In his definitive 1994 history of the soft-drink giant, "Secret Formula," Allen notes bank executives themselves expressed concerns during the past half century about the bank's heavy concentration of Coca-Cola stock, calling it "our problem" and worrying about their vulnerability to lawsuits for not diversifying.

"In my view, it was just inevitable that something like this would come along because there's a collision of interests," Allen said. However, he added, numerous people and institutions in Atlanta have benefited enormously in the past from overconcentrations in Coke stock.

The plaintiffs, who live in New York, are asking for punitive damages of 10 times the $15 million figure, plus the repayment of fees paid SunTrust and other damages for a total of at least $165 million.

During the time period in question, from July 1998 through the end of May 2005, Coca-Cola stock fell about 43 percent to around $44 a share from about $77 a share.

SunTrust went to court against the plaintiffs pre-emptively in March in Fulton County Superior Court, asking that the bank be allowed to resign as trustee from the trusts in question.

In response to the lawsuit filed against the bank in May, SunTrust said in a statement: "As with any lawsuit, there are two sides to every story and we look forward to telling ours in the proper forum. We believe these allegations are without merit."

The case involves a trust created in the 1940s by Sauls, a distinguished Atlanta doctor. Sauls' collection of medical books were donated to Piedmont Hospital upon his death in 1947, and formed the basis of the hospital's medical library.

Sauls had ties to Coca-Cola's Candler and Woodruff families. The assets of the trust were primarily in Coca-Cola common stock and Sauls designated Trust Co. of Georgia, Coca-Cola's bank, which now is known as SunTrust, as trustee.

In 1999, the trust was divided into multiple trusts. Beneficiaries included family members and Emory University.

Shares of the beverage company stock recently have averaged about 66 percent of the market value of the trusts, according to the complaint.

The lawsuit states that in 1995, after the death of their mother, Caroline Sauls Hitz Shaw, plaintiff Hitz began voicing concerns to SunTrust about the concentration of Coca-Cola stock in the trusts.

Hitz also wrote a letter to SunTrust in the summer of 1998 expressing his worries and continued to request diversification in ensuing years.

According to the complaint, the beneficiaries "were repeatedly informed by SunTrust that significant diversification was not necessary, because Coca-Cola was, in SunTrust's own words 'good company;' because Coca-Cola is a 'diversified company;' and because Coca-Cola stock will 'come back.' "

The plaintiffs claim neither the language of the original trust nor the language of any related documents instructed SunTrust to keep the trusts in Coca-Cola stock.

The complaint also states that between 1998 and present, as the value of their trusts fell, SunTrust charged the beneficiaries nearly a quarter of a million dollars.

The plaintiffs claim SunTrust and Coca-Cola's close ties are to blame, saying SunTrust's own holdings give it an incentive not to sell the Coca-Cola stock on behalf of its trusts — protecting the value of its own investment.

"SunTrust's massive holdings of Coca-Cola stock for its own account make SunTrust incapable of providing prudent, independent and impartial judgment to the beneficiaries with respect to Coca-Cola stock held by the trusts," according to the complaint.

Further, the plaintiffs claim the fact SunTrust's management must answer to a board of directors containing members with significant ties to Coca-Cola, creates additional conflict "and the temptation to consider the objectives of SunTrust's board of directors (which include Coca-Cola executives) rather than the best interests of the beneficiaries."

E. Neville Isdell, chairman and CEO of the beverage company, is a SunTrust board member; M. Douglas Ivester, retired chairman and CEO of Coca-Cola is a SunTrust board member; and James B. Williams, former chairman and CEO of SunTrust is a board member of Coca-Cola. For some portion of the time period in question, Williams served on both boards.

The close ties are nothing new, said Coca-Cola historian Allen.

At any time in the 1940s and 1950s, at least a half-dozen Coca-Cola directors served on Trust Co.'s board, "guaranteeing the company's interests would be protected," according to Allen's history of the beverage company.

In the book, Allen also writes that Hughes Spalding, a Trust Co. director and personal attorney to then-Coca-Cola head Robert Woodruff, would notify Woodruff whenever an investor planned to sell Coca-Cola stock, and Woodruff would move to keep the stock in "friendly" hands.

"It's a very close relationship," Allen said.

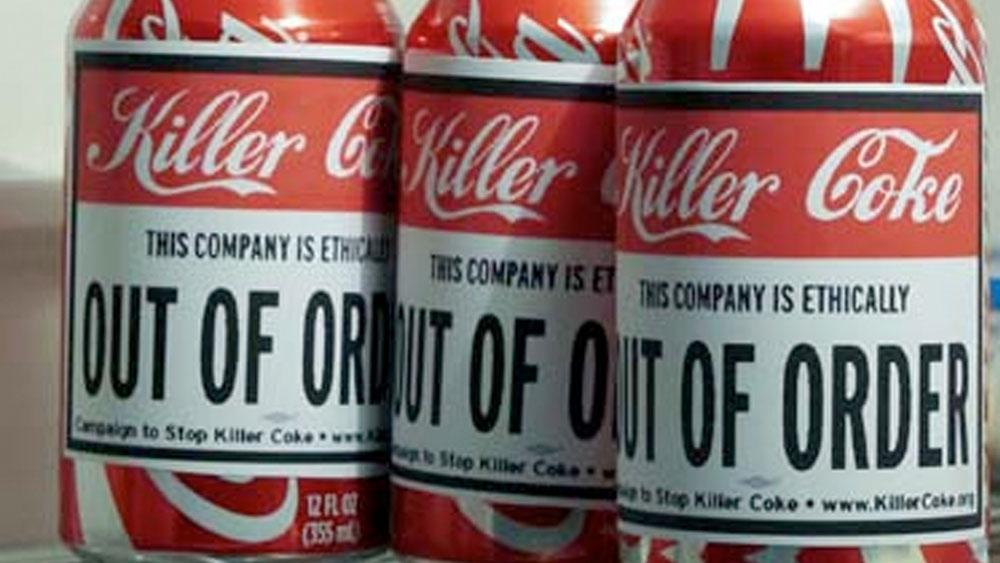

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.