Coke, Pepsi lose fight over labels

Knight Ridder News | 12/09/04

ATLANTA, Ga. — A ruling by India's highest court means Coca-Cola and Pepsi products sold in the country may soon have to carry labels that warn consumers the soft drinks may be contaminated with pesticides.

While the giant American companies have argued for months that the products they sell in India are safe, the ruling could cause problems for their operations in this fast-growing market.

India's Supreme Court gave the Indian units of Coke and Pepsi two weeks to work with a lower court to come up with language for the labels, according to media reports from India.

The labeling issue is the latest development in a controversy that dates to August 2003, when an environmental group found pesticide residues Coke and Pepsi products that exceeded European Union standards.

The Center for Science and Environment targeted Coke and Pepsi as part of larger efforts to focus on environmental problems in the world's second-most populous nation.

The controversy is a reminder of India's sometimes acrimonious relationship with huge multinational companies. While many food and drink products sold in the country are contaminated, Coke and Pepsi have been major targets in part because they are well-known foreign companies that draw plenty of attention.

Indians this month marked the 20th anniversary of the world's worst industrial accident in Bhopal, which involved a large multinational company. A Union Carbide plant spewed 40 tons of deadly methyl isocyanate gas after one of the storage tanks burst, killing at least 4,000 people.

The Supreme Court's decision on Coke and Pepsi made headlines in India. According to a report from the Times of India, Harish Salve, an attorney who represented the soft drink makers, said pesticide traces come from water supplies and sugar from crops raised with the use of pesticides.

Sameer Mathur, operations manager for Big Bazaar, a one-stop shop in an upscale suburb of New Delhi, said warning labels might help Coke and Pepsi in the long run.

"The moment you put that label on, you are assuring consumers about your product," he said in a phone interview with the Journal-Constitution. "Look, there are all sorts of warnings on cigarette packs, but they don't frighten away smokers, do they?"

Coke maintains its products in India are "world class and safe."

"We follow one quality system across the world," said company spokesman Ben Deutsch in Atlanta. "The treated water used to make our beverages across all our plants in the country already meets the highest international standards, including EU."

Pepsi officials said they hadn't seen the official court ruling, and spokesman Dick Detwiler said it was still not clear what might be required of the bottlers.

"What is clear is that our products in India are absolutely safe and that they are made in accordance with Indian and international standards," Detwiler said.

People who have studied Indian agriculture say pesticide contamination is a growing problem and an issue for many products.

Ramesh Kanwar, an Indian native who heads the agricultural and biosystems engineering department at Iowa State University, said contamination is likely to increase as agriculture becomes more concentrated and farmers pour pesticides on their crops.

Iowa State is one of six American schools working with an Indian university to study agricultural issues, including water use practices. The soft drink controversy is a small matter, Kanwar said, but it gets a great deal of attention because Coke and Pepsi are big-name, multinational corporations.

"They always get targeted," he said.

Sunita Narain, director of the Center for Science and Environment, has said the environmental advocates intended to put a spotlight on poor regulations.

"The key issue is that there are no final product standards," she said last year in response to questions from the Journal-Constitution.

Mathur, the store manager in New Delhi, said he believes Indians are willing to accept higher levels of contamination in drinks and other products than Europeans or Americans are because "no one expects the water here to be as clean."

"We know there is a lot of agricultural production here and there is groundwater contamination," Mathur said. "The bottom line is nobody is falling sick."

Young tech professional Subhendu Aich and his friend, Tushar Lahiri, both of Calcutta, said a warning label won't be enough to wean them off their favorite drinks.

"We have seen the news," Aich said, "but it won't affect our habits. We love Coke and Pepsi."

Srinivas Reddy, who grew up in India and now directs the University of Georgia's Coca-Cola Center for Marketing Studies, also doesn't think warning labels will hurt soft drink sales in the long run.

"It's going to have some sort of a dampening effect until the market absorbs it," Reddy said. But if someone has been drinking Coke or Pepsi for years without health problems, he said, the warning might go ignored.

How it all plays out is important to Coke and Pepsi, since India is a giant market.

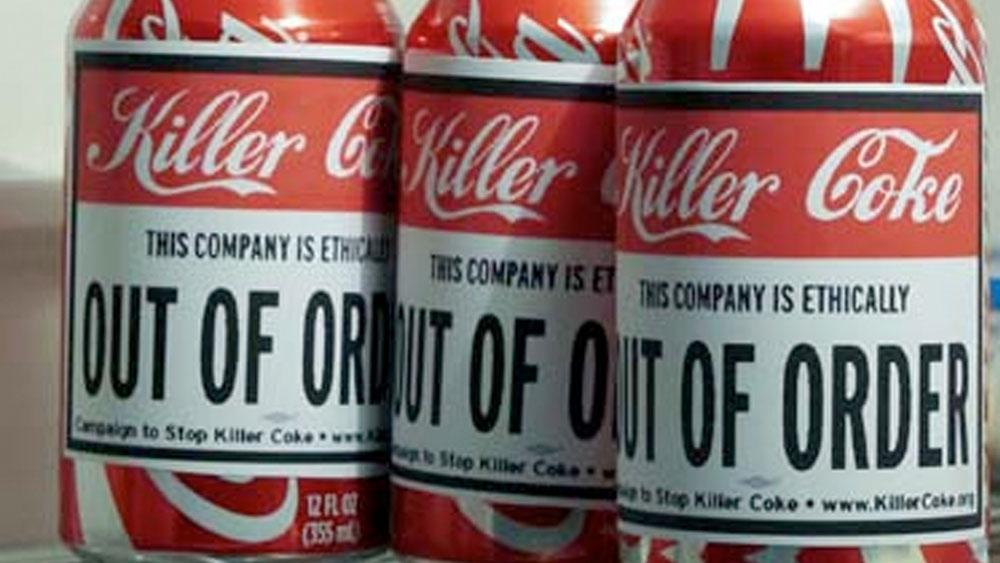

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.