All Is Not Sweet at the Home Base of Coca-Cola

By BY CLAUDIA H. DEUTSCH | The New York Times | September 28, 2004

Read Original

In late June, just a few weeks after coming out of retirement to become the Coca-Cola Company's latest chief executive, E. Neville Isdell visited Coke's regional managers in China. He remembers one in particular, a young woman named Lily, on the job less than three years and radiating zeal and spunk. "She reminded me of myself at her age, just full of enthusiasm for the business and the brand," Mr. Isdell, 61, said.

Fast-forward to Sept. 15, the day Coke warned investors that this year's earnings would be lower than they had expected. Mr. Isdell walked through Coke's Atlanta headquarters, and the miasma of gloom was palpable. "No one would make eye contact with me," he recalled. "The trust has been broken, and the culture needs regeneration."

Indeed it does. Despite the earnings alert, Coke is doing fine financially. It generates billions of dollars in cash, its balance sheet is strong and its earnings, while declining, remain solid (Coke expects to earn 46 cents to 48 cents a share in the third quarter, down from 50 cents in the comparable period last year). Its business — "we're in the industry of wetting throats," as Mr. Isdell put it #151; is certainly not threatened with technological obsolescence. And overseas, from what Mr. Isdell could tell in a recent multicountry tour, morale seems intact.

But in Atlanta, Coke's home base, its cultural health is a lot less robust. North America provided just 30 percent of last year's $21 billion in sales and only about 20 percent of its operating profits — $6 billion after subtracting corporate overhead costs. Still, the decisions made in Atlanta ripple out to the entire system. "If the motherland is not working properly, it sets a bad tone for the rest of the world," said William Pecoriello, a beverage analyst at Morgan Stanley.

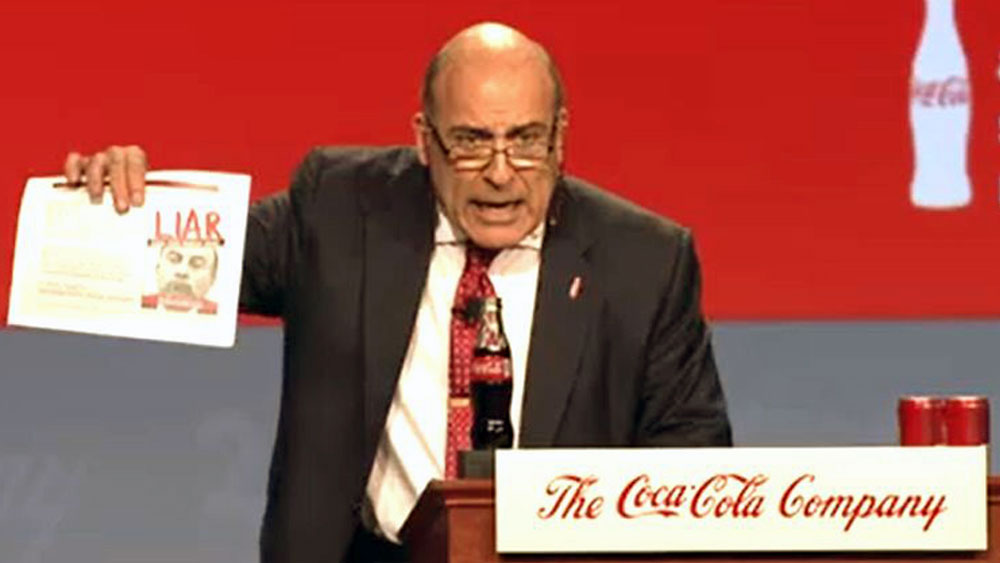

E. Neville Isdell, the chief executive of Coca-Cola, right, said that he had made hiring new people and training remaining ones top prioorities at the company

The motherland is in turmoil. Analysts say that political infighting at the top, between top executives and powerful directors like Donald R. Keough, and among top executives themselves, has turned Coke's executive suite into a revolving door. Its president, Steven J. Heyer, quit after he was passed over for the chief executive's job. Coke has a new marketing chief, a new human resources officer and a new executive overseeing relations with bottlers.

"Neville may be one of the few people who can really restore aggressiveness, competitiveness and pride," said John D. Sicher, editor and publisher of Beverage Digest.

The lower ranks at Coke are in turmoil as well. Coke laid off about 2,500 people in the United States in 2000, and it cut an additional 1,000 American jobs this year. Mr. Isdell concedes that many Coke workers, most of whom had considered job security to be part of their tacit contract, now worry they will be cut, too. And that worry is hitting at a time when their Coca-Cola stock — long a major portion of compensation at Coke — is trading at less than half its peak of $88 in 1998. Shares of Coca-Cola closed at $39.63 yesterday, down 36 cents.

Last week, Mr. Isdell reaffirmed his own faith in the company's future: he bought 100,000 shares at an average price of $40.57, bringing his total holding to about 340,000 shares. Outside investors are not so sanguine. They note that the market for carbonated drinks has been growing less than 1 percent a year since 1998 and many say that Coke is unlikely ever again to deliver the 10 percent annual earnings growth that used to be standard.

"Management is reluctant to let go of the idea that Coca-Cola is a growth company, but the investment community's expectations for growth have slowly been ratcheting down," said Timothy M. Ghriskey, chief investment officer of Solaris Asset Management, which sold its Coke stock in the late 1990's.

Mr. Isdell himself says that innovation in products, packaging and marketing has been flagging at Coke. The exodus of people, he has publicly conceded, has left Coke with a "weakened bench" — a paucity of trained marketers, financial whizzes and others to step up to the plate if more people leave.

Mr. Isdell says the employees acknowledge the problem themselves. "We asked the staff what was wrong and what was right around here," he said. "The biggest complaint was that we're not giving enough development." He said he had made hiring new people, and training remaining ones, top priorities.

Rebuilding Atlanta's esprit is not Mr. Isdell's only pressing task, of course. Coke's relationship with its bottlers — the companies that buy concentrate from Coke and then sell products to the retailers — has always been fraught with tension. After all, the more Coke charges for syrup and the less it pumps into marketing campaigns, the higher its profits — and the lower those of its bottlers.

But this month Coca-Cola Enterprises, Coke's main North American distributor, issued its own earnings warning, and the tension has reached a fever pitch. Some analysts have even suggested that Coke, which owns about 40 percent of the bottler, buy the entire company.

Mr. Isdell would say only that negotiations over concentrate prices and other issues were continuing. But analysts question whether he is harnessing the power of the bottlers.

"They have the best global distribution network, but their lukewarm record on noncarbonated beverages shows they are not utilizing it well," said B. Craig Hutson, senior bond analyst at Gimme Credit, a fixed income research firm.

It is no minor issue. Sugared soft drinks still sell well in the developing world. But in North America and parts of Europe, the fear of obesity has tarnished the empty calories associated with regular soft drinks, while the emphasis on health and fitness has put a pall on the artificial sweeteners in diet drinks.

Coke recently tried to carve out a middle ground with C2, a midcalorie product. Mr. Isdell insists that "C2 was never meant to be a blockbuster," and that its sales have been on track; analysts say the product was priced too high and packaged badly and it landed with a thud. They note that Coke's Powerade sports drink, Minute Maid juices and Dasani water lag behind the Gatorade drinks, Tropicana juices and Aquafina water of the rival PepsiCo.

"Coke needs to develop better alternative beverages, and better ways to get cola drinks into the hands of new drinkers," said Marc Cohen, an analyst with Goldman Sachs.

Analysts say that Mr. Isdell's background — he spent 35 years in the Coca-Cola system — may help him do that. Just as important, they say that he is far more accessible to employees, and interested in day-to-day machinations, than was his predecessor, Douglas N. Daft.

"Neville's engaged with his job, he's hard working, and he radiates decency and likability," Mr. Sicher of Beverage Digest said. "He knows the company needs fixing, and he has the ability to do it."

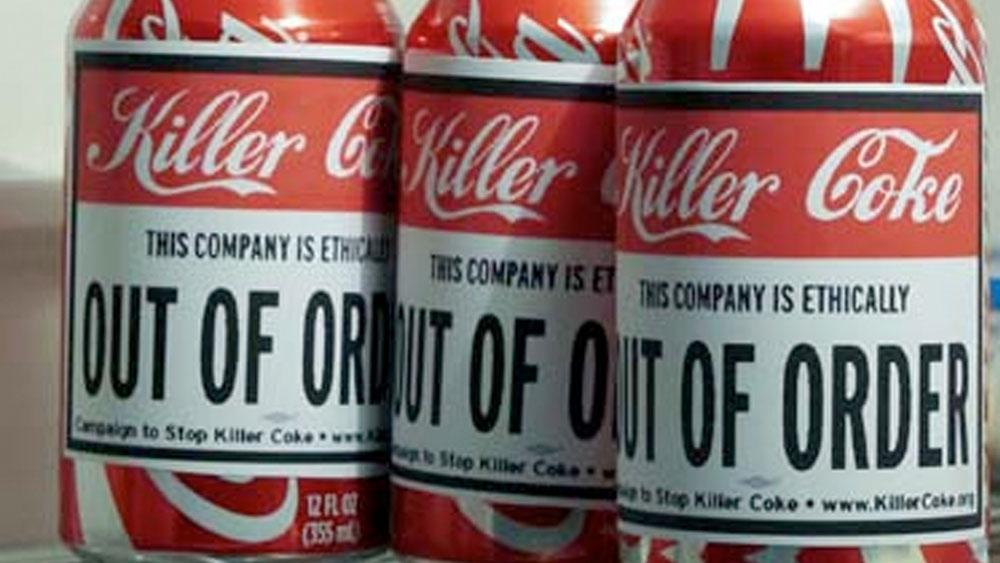

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.