As Bloomberg Fought Sodas, Nominee Sat on Coke Board

By MICHAEL BARBARO and ANEMONA HARTOCOLLIS | New York Times | November 16, 2010

Read Original

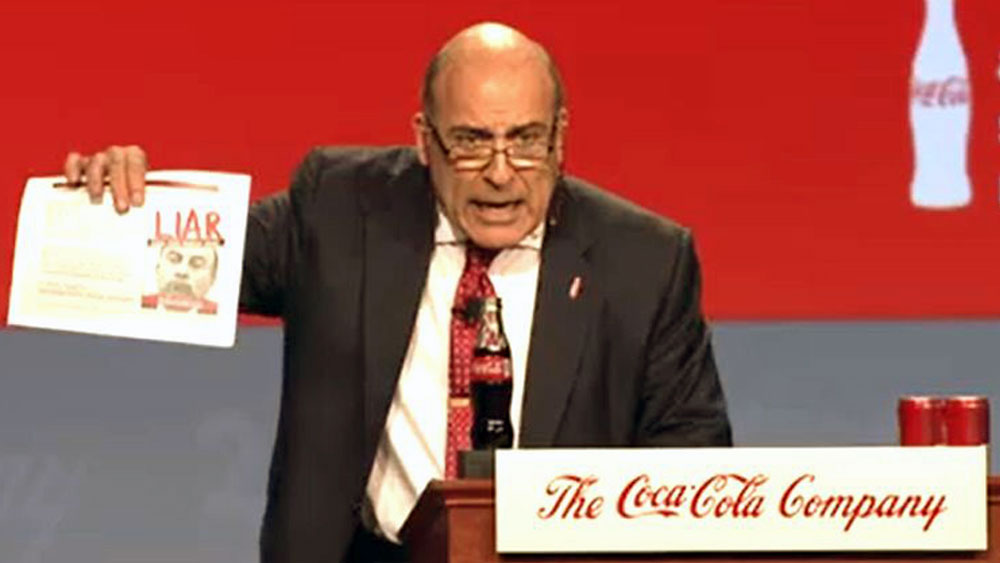

Cathleen P. Black, left; Douglas Daft, then chairman of Coca-Cola; Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani; and James Robinson III and Herbert Allen, New York-based Coke board members, in 2001.

(Photo by Michael Pugh/Coca-Cola, via Associated Press)

By her own account, Cathleen P. Black, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg's choice to be the next New York City schools chancellor, has had almost no experience with the public education system.

But for nearly 20 years, she played an influential role in a company that did: Coca-Cola.

As America awoke to a national obesity epidemic and schools tried to rid their hallways of sugary drinks, Coca-Cola emerged as the biggest and most aggressive opponent of the scientists, lawmakers and educators who tried to sound the alarm.

The company unleashed a flurry of lobbyists, donations and advertising to fight the efforts, prompting local officials to describe it as "bullying" and "unconscionable." Even as other large food manufacturers embraced the public-health measures, Coca-Cola dug in its heels, rewarding schools that kept selling its products and threatening those that would not, officials said.

Through most of these battles, Ms. Black, the magazine executive nominated last week to lead the nation's largest school system, was one of 14 people on the company's board of directors, and she sat on a company committee that focused on policy issues including obesity and selling soda to children. On a board that meets six times a year, she was privy to internal debates about the company's combative strategy, and there is no public evidence that she ever questioned it.

"I don't think we've gone to a single meeting in the last two years where we haven't discussed that issue," said Donald McHenry, a longtime Coke board member and a professor at Georgetown University who sat on the committee with Ms. Black.

Mr. McHenry would not characterize Ms. Black's views on the topic, and she has declined interview requests since she was tapped. A spokesman for Coca-Cola and a spokesman for the city both declined to discuss Ms. Black's role in the debate over how to handle the issue of sodas in schools.

Ms. Black resigned from the Coke board this week, citing potential conflicts of interest, but her time at the company is especially striking because the man who chose her for the schools job has declared soda an urgent public health menace and has plastered the city's subway cars with advertisements that liken drinking it to ingesting goopy liquid fat.

"Normally, I would think that somebody who served for 18 years on the board of this junk-food producer is tainted," said Michael Jacobson, executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

"If you're judged by the people with whom you hang out, it's not a good sign," said Dr. Jacobson, whom Mr. Bloomberg recently nominated for a national health "hero award" and who received it last month. "But I wouldn't say it's disqualifying. I don't know what role she played on the board. It could be she was pushing them to cut the sugar or sell fruits and vegetables. It's hard to know."

He added, "I don't want to be naive, because I don't know what she pushed for, if anything -- or was it easy money?"

Asked about the apparent conflict between Mr. Bloomberg's views and the work of his nominee, a spokeswoman for the mayor reiterated his opposition to the sale of sugary drinks in schools and his support of Ms. Black, saying the policy would continue under her chancellorship.

In nominating Ms. Black, Mr. Bloomberg said she would bring corporate innovation and management savvy to the sprawling system. But her record at Coca-Cola shows she will bring corporate baggage as well.

Ms. Black had been on the board since 1990, except for a brief leave, earning well over $2.1 million in cash and stock over the years, according to Equilar, which studies corporate pay. (Her current stock holdings in Coca-Cola are worth $3.3 million.)

During Ms. Black's tenure, pressure intensified on soda companies to limit sales in schools after Dr. David Satcher, the surgeon general, in 2001 declared obesity a national crisis with "tragic results." He urged local communities to lead the fight. And much to the beverage industry's chagrin, they did.

In 2003, California and New York City banned the sale of soft drinks in elementary and middle schools. At the same time, a coalition of lawyers who had successfully sued tobacco companies began developing strategies for taking on food companies, threatening a barrage of lawsuits.

By 2006, when Connecticut tried for the second year in a row to join the wave of local governments barring sugary drinks at schools, Coke and other companies pumped hundreds of thousands of dollars into a bare-knuckle battle to stop the legislation.

According to Connecticut state officials, Coke lobbyists warned school districts that if the legislation passed, Coke would stop providing money for after-school programs, which it had done in exchange for the right to put vending machines on campus.

State Senator Donald E. Williams Jr., who sponsored the legislation, recalled that company representatives "targeted urban legislators and reminded them that the soda companies often contributed significant amounts of money to schools to buy scoreboards and to supplement their needs." (At the time, Coke denied making any threats.)

The fight in Connecticut put a harsh spotlight on Coke's longstanding practice of rewarding school districts for exclusive contracts to sell its beverages. Lawmakers revealed that Coke paid a higher commission to schools for the sale of carbonated drinks than for juice or water. And they showed that the company dispensed "marketing bonuses " to districts that signed on, including free supplies of sports drinks and Coke-branded coolers to be placed on the sidelines at athletic fields.

Connecticut's attorney general, Richard Blumenthal, called the strategies "unconscionable." The state law was enacted by a slim margin.

About the same time, under pressure from the growing tide of state legislation and the intensifying threat of lawsuits, Coke eventually agreed to not sell sugary soda in American schools (the agreement allowed diet sodas and sports drinks to still be available in high schools).

But it was not long before Coke once again pushed the envelope. This March, the leading soda makers seemed to reached a milestone agreement to stop selling sugar-laden drinks to schools around the world, bowing to critics who argued that the companies were still exploiting children in emerging markets like India and China.

But while Pepsi said it would keep the drinks out of all schools, Coke carved a loophole, conspicuously reserving the right to sell them depending on local demand. "Shame on Coca-Cola," proclaimed the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

"High school students everywhere deserve the same help as American high schoolers," the group said.

In New York, where Ms. Black is the chancellor in waiting, her likely new boss, Mr. Bloomberg went well beyond school grounds, trying to curtail soda consumption with a new statewide tax on sugary drinks.

Coca-Cola and Pepsi bottlers, joined by the American Beverage Association, a trade group, spent heavily on an elaborate television campaign featuring hard-up mothers and children stocking the family refrigerator with beverages. The proposal was defeated.

Mr. McHenry, the Coke board member, said he opposed the efforts, like those in New York City, to single out individual products and companies as an unfair overreaction. "The ads in New York City and the approach in New York City is not fact-based," he said. "It's good publicity, but I just think it's poor science."

Asked how Ms. Black might handle the issue as chancellor, he said, "I am sure Cathie's effort is the same as mine would be: to make sure that people make policy on the basis of science and facts, and let those things guide you."

David M. Halbfinger contributed reporting.

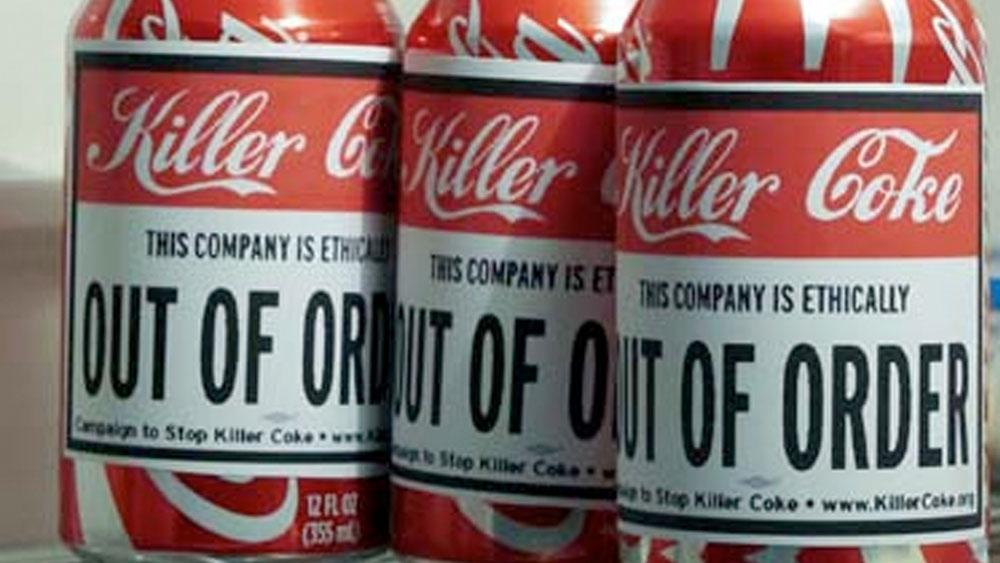

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.