Obesity Inc.: The Food Industry Empire Strikes Back

By Melanie Warner | The New York Times | 7/7/05

Read Original

Late-night comedians had a field day in the summer of 2002 when a lawsuit accusing McDonald's of making two teenage customers in New York fat and unhealthy was filed.

But thousands of restaurant owners were not amused: Pelman v. McDonald's was the second time in a month that lawyers had tried to hold food companies responsible for America's obesity crisis.

Food and restaurant companies, fearing they would be hammered with enormous judgments, as the tobacco industry was, immediately began fighting back, waging an aggressive campaign to make it impossible for anyone to sue them successfully for causing obesity or obesity-related health problems.

Almost three years later, they have had astounding success. Twenty states have enacted versions of a "commonsense consumption" law. They vary slightly in substance, but all prevent lawsuits seeking personal injury damages related to obesity from ever being tried in their courts. Another 11 states have similar legislation pending.

Although plaintiffs' lawyers are confident there are ways around the new state laws, the measures, along with a class-action overhaul bill President Bush signed into law this year, will probably make it harder for lawyers in obesity cases to win the kind of large awards seen in tobacco cases.

The National Restaurant Association, based in Washington, and its 50 state organizations, which represent large chains like McDonald's and small independent businesses, led the campaign. In most states, lobbyists for food companies and restaurants helped write the legislation and did much of the legwork in state capitols.

Restaurant owners and food company executives personally visited state lawmakers, testified at hearings and steered campaign contributions to pivotal lawmakers. Executives from Kraft and Coca-Cola showed up in Texas, for instance, to lobby for that state's commonsense consumption bill, which was signed into law by Gov. Rick Perry last month.

According to data from the Institute on Money in State Politics, a nonpartisan research group based in Helena, Mont., in the 2002 and 2004 election cycles, the food and restaurant industry gave a total of $5.5 million to politicians in the 20 states that have passed laws shielding companies from obesity liability.

Adoption of commonsense consumption laws by almost half the states reveals how an organized and impassioned lobbying effort, combined with a receptive legislative climate, can quickly alter the legal framework on a major public health issue like obesity.

Consumer advocates, who knew about the state efforts but were preoccupied trying to prevent similar measures from being enacted on a national level, are not pleased. Michael Jacobson, executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, calls it "shameful" that food companies are trying to get special exemptions from lawsuits.

"If someone is saying that a 64-ounce soda at 7-Eleven contributed to obesity, that person should have his day in court," Mr. Jacobson said. "If it's frivolous, the courts are accustomed to throwing those out."

Tom Foulkes, the director of state relations at the National Restaurant Association, says his group and related state organizations are giving the American public what it wants. He points to a Gallup poll from 2003 showing that 89 percent of people say they do not support obesity lawsuits against fast-food companies.

In Colorado, Pete Meersman, president and chief executive of the Colorado Restaurant Association, started pushing for an obesity lawsuit bill after attending a conference organized by the National Restaurant Association in July 2003. The conference gathered executives from all 50 state organizations; the looming threat of more obesity litigation was a central topic.

"We wanted to make sure that frivolous lawsuits like this never made it to the discovery stage, which is where these things get expensive for businesses," said Mr. Meersman, referring to Pelman and an earlier lawsuit filed by the same lawyer that also named KFC, Burger King and Wendy's as defendants.

Acting on behalf of members ranging from Arby's to Fatty's Pizza, Mr. Meersman sprang into action. After several preliminary talks with state legislators, a lucky break came in September 2003 during a visit to Washington. Mr. Meersman had scheduled a meeting for himself and 20 restaurant executives with Representative Joel Hefley, a longtime Republican congressman from Colorado Springs, to talk about various legislative issues. Mr. Hefley's wife, Lynn, a representative in Colorado's state legislature, happened to be in her husband's Capitol Hill office. When the subject turned to obesity lawsuits, her ears perked up.

"She was quite vocal about it," Mr. Meersman recalled. "She couldn't believe this kind of stuff was going on, people suing companies for making them fat." After that meeting, Mrs. Hefley signed on as an ardent sponsor of Colorado's commonsense consumption bill.

But her office did not draft the legislation. That job went to Mr. Meersman, who spent several weeks coming up with the right language. When he completed a first draft, he showed it to Mrs. Hefley, who added some wording on personal responsibility. He also solicited the views of companies like Outback Steakhouse and Texas Roadhouse, which gave their approval.

Mr. Meersman later added language to prevent someone from claiming that the continued consumption of a food caused not just obesity, but also cancer, diabetes or other such chronic illness. Mr. Meersman also testified in the bill's favor, arguing that obesity lawsuits would do nothing but cost companies a lot of money and clog up the courts.

The bill passed in May 2004 by a vote of 60 to 3 in the Colorado House and 33 to 2 in the state Senate.

While Mr. Meersman and Mr. Foulkes see this as good old-fashioned lobbying, some critics say the process is flawed. "It's unnerving to think that public laws are being crafted by corporate interests that simply hand language over to a lawmaker to insert in a bill," said Larry Noble, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics. "These bills are intended to protect the industry, not the public."

The National Restaurant Association is also working on the federal level with Representative Ric Keller, a Republican from Florida, and Senator Mitch McConnell, a Republican from Kentucky, to get a national "cheeseburger bill" passed. This bill, which would prevent obesity lawsuits from going forward in either federal or state courts, stalled in Congress last year and faces an uncertain future.

As the country grapples with the doubling and tripling of obesity rates in the last 25 years, the food industry stands firmly against efforts to make food or restaurant companies legally accountable for the problem. The National Restaurant Association and the 50 state associations lead a coalition of food industry interests, including the Grocery Manufacturers Association, the American Beverage Association and the Food Products Association.

Much of the food and restaurant industries acknowledge that obesity is a serious public health issue; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 30 percent of American adults are obese and at risk for a host of associated disorders like heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure and arthritis. But the industries maintain that the best way to address this problem is through voluntary actions and consumer education.

"Our members are making a whole range of changes, everything from adding more fruit and salads to menus, to offering whole wheat bread as an option and selling more bottled water," said Sue Hensley, a spokeswoman for the National Restaurant Association. "Lawsuits are just not productive."

Many trial lawyers disagree - especially those who have worked on tobacco litigation and have watched national smoking rates decline. They say lawsuits are an effective way to get food companies to change the way they operate and the kinds of products they sell. Since the surgeon general issued a "call to action" in 2001, warning that obesity could wipe out many of the health gains Americans have achieved in recent decades, the plaintiffs' bar has been threatening to turn food into the next tobacco.

The industry's success at the state level is another blow to that effort. Trial lawyers were hit this year by the Class Action Fairness Act, an initiative intended to prevent trial lawyers from shopping for the most favorable states to bring their cases. The law will force class-action lawsuits with plaintiffs living in a state different from the defendant or those seeking more than $5 million in damages into federal courts where large awards are less common. A more comprehensive liability-overhaul bill is still working its way through Congress.

But trial lawyers say they will not be deterred. They voice confidence they can get around both the class-action overhaul law and the new state laws.

Richard A. Daynard, a professor at Northeastern University School of Law and a founder of the antitobacco movement, says that while the new state laws kill the possibility of personal injury obesity cases in those 20 states, they do not preclude another, perhaps more easily provable, type of litigation that lawyers have their sights on.

"Rather than seeking personal injury damages for the consequences of obesity, there will be lawsuits based on state consumer protection laws," said Professor Daynard, who heads the Obesity and Law Project at the Public Health Advocacy Institute at Northeastern. "There's a lot of deception in the marketplace and a lot of it is relevant to the obesity epidemic. But here we don't have to prove anyone got fat."

These suits, however, are less likely to provide huge tobacco-size financial awards.

John F. Banzhaf, a George Washington University Law School professor and an outspoken supporter of tobacco litigation, said that thwarting class-action overhaul would be easy because state suits did not necessarily need to be class actions.

"The tobacco industry is reeling with big verdicts in both class actions and individual suits," said Professor Banzhaf, who is an adviser to the plaintiffs' lawyer in Pelman v. McDonald's, which is about to enter the discovery stage.

The initial personal injury claims in that lawsuit - which contended that Ashley Pelman and Jazlyn Bradley were harmed by their frequent consumption of McDonald's food - were tossed out by the judge. But the restaurant industry suffered a setback in late January when a panel of three federal appeals judges reinstated one aspect of the suit - a deceptive-practices claim, stating that McDonald's falsely presented its food as nutritionally beneficial to consumers.

Three days later, McDonald's chief financial officer, Matthew H. Paull, told investors that the company was setting aside new reserves for legal charges, though he did not say how much or if the funds were being earmarked for the obesity lawsuit. Professor Banzhaf acknowledges that public opinion is not currently in favor of obesity litigation. But he added that the situation for tobacco was similar 15 years ago when people began suing cigarette companies for making smokers sick.

"People laughed and said, 'You won't even get one of these cases to a jury,' " Professor Banzhaf recalled. "Today it's, ho hum, there's another verdict."

Professors Banzhaf and Daynard say they and other lawyers are willing to be patient, because they believe that public sentiment will shift when people learn the elaborate ways in which companies market products they may know to be unhealthy, especially products aimed at children.

"People changed their minds when documents started to come out about how tobacco companies misled customers about the alleged health benefits of light and low-tar cigarettes," Professor Daynard said. "Similarly, people will start to realize that Ronald McDonald is not their friend."

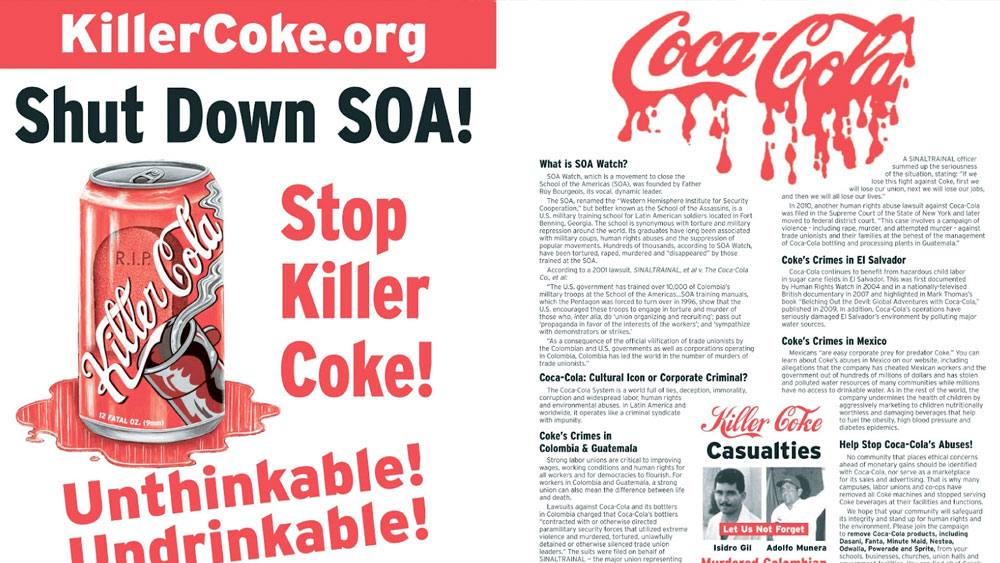

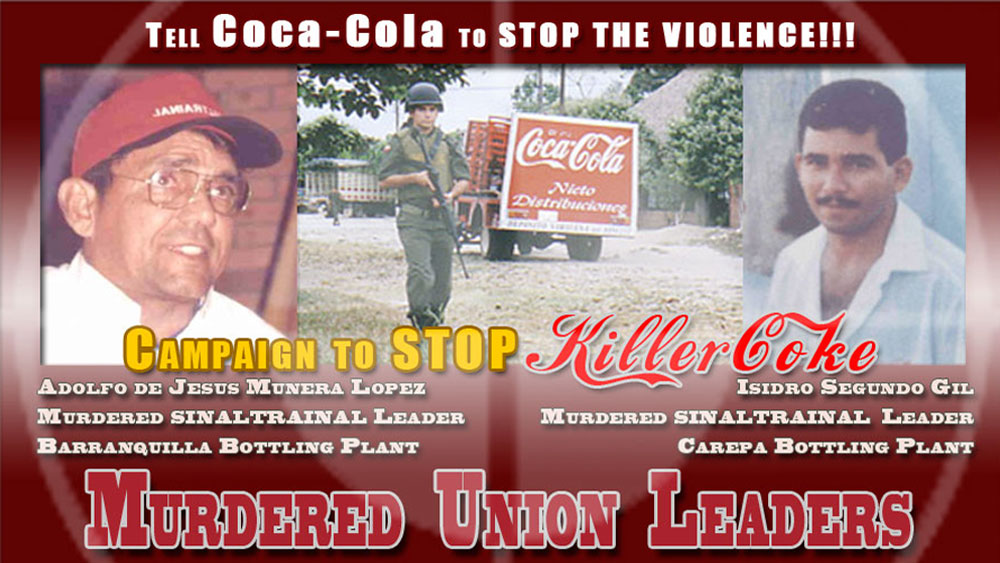

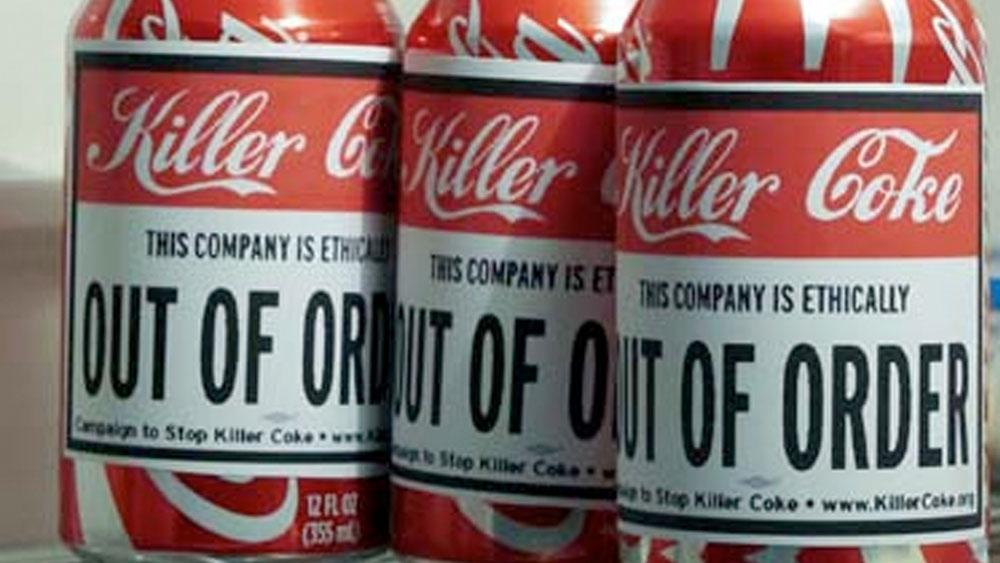

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.