Bottled up: why Coke stands accused of being too cosy with the Karimovs:

A dispute with a former partner in an Uzbek plant highlights a risk for multinationals operating in errant countries, writes Edward Alden

By Edward Alden and Andrew Ward| Financial Times | 6/14/06

For nearly a decade, Coca-Cola's bottling plant in Uzbekistan was a shining example of the successful strategy that has seen the company expand into more than 200 countries around the world.

The plant on the outskirts of the capital Tashkent, set up in 1992 and run under a joint venture with ties to the family of Islam Karimov, the Uzbek strongman, was twice selected as Coke's "bottler of the year" in its Eurasia and Middle East region and was highly profitable, with volume growth of about 10 per cent annually.

But all that began to unravel five years ago, when the marriage between Mansur Maqsudi, Coke's main partner in the plant, and Gulnora Karimova, the president's Harvard-educated daughter, fell apart — in recriminations that are still being felt by the couple, their children and the Coca-Cola company.

Mr Maqsudi last week filed for binding arbitration at an Austrian tribunal, under a provision of the original joint-venture agreement with Coke, seeking more than Dollars 100m (Pounds 54m, Euros 79m) in damages from the company. He alleges that it "undertook to conspire with Uzbekistan" to strip him of his share in the plant. Coke insists it did not collaborate with the government, saying the arbitration will vindicate that.

At the heart of the case is the question of what obligations a multinational faces in operating in countries where human rights abuses are common and there are few legal protections. The issue of what Coke should or should not have done in Uzbekistan will also focus fresh scrutiny on the company's conduct around the world and provide new ammunition for its numerous critics.

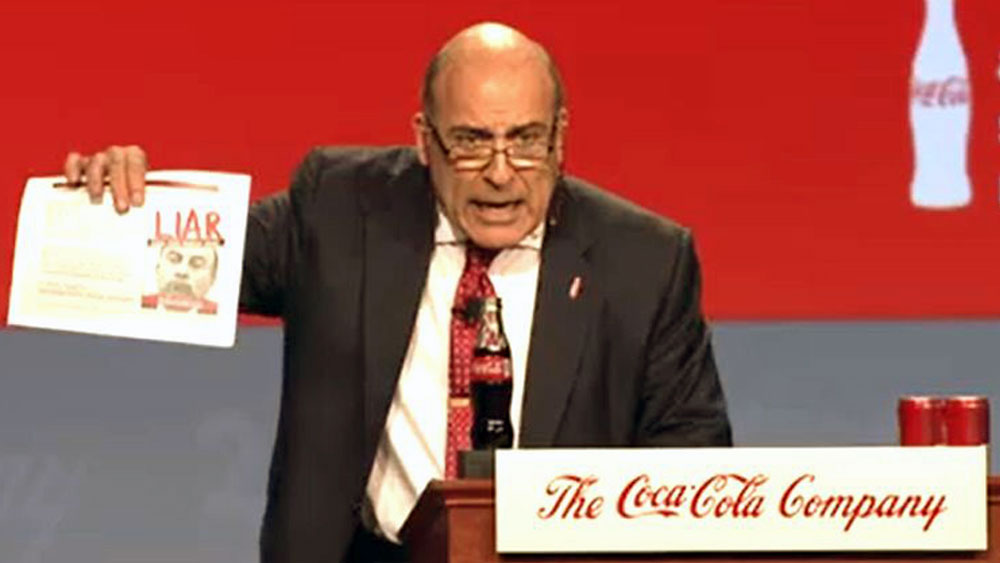

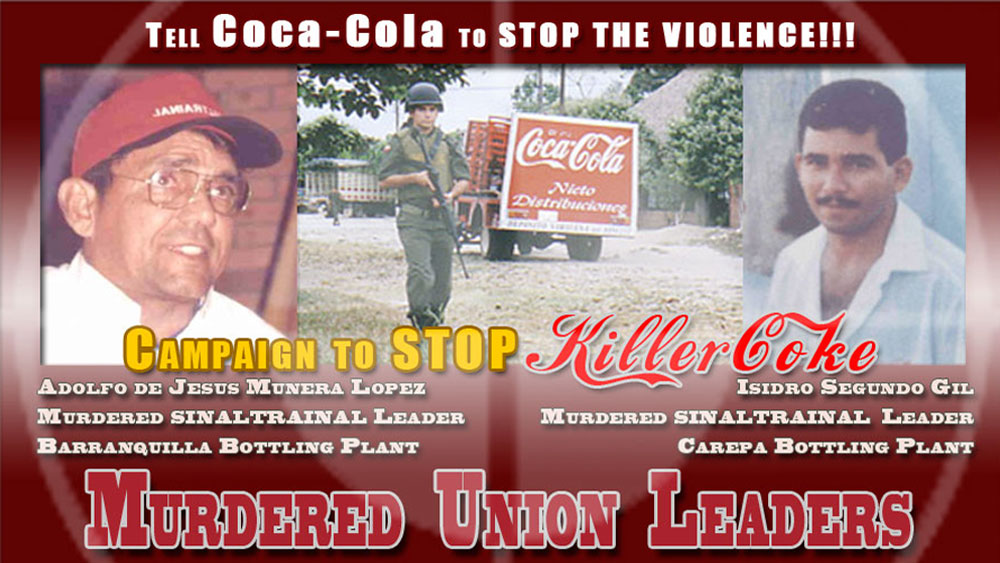

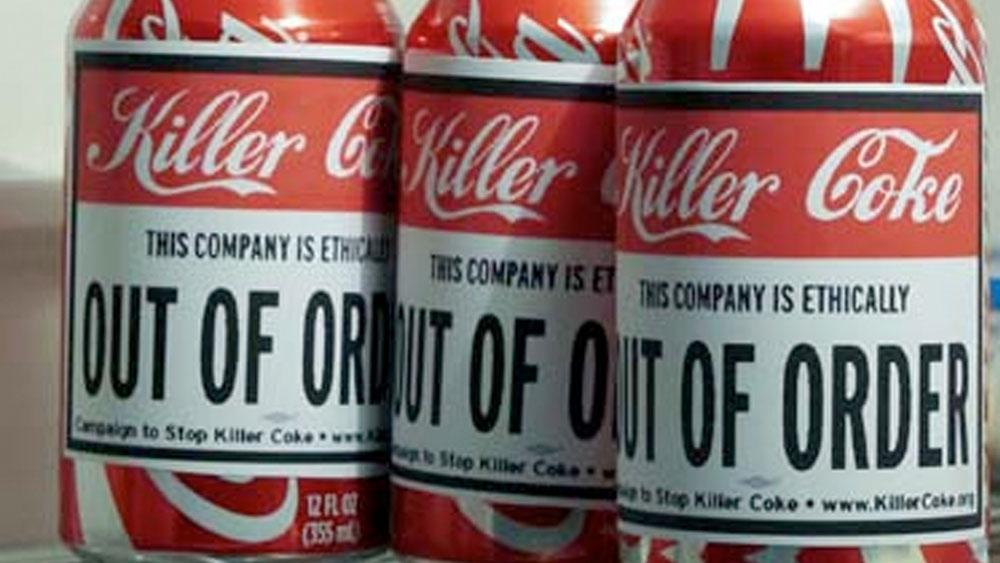

Coke is already facing a US lawsuit brought by labour rights groups over allegations that it turned a blind eye to the murder of union leaders at its bottling plants in Colombia by rightwing paramilitaries. A similar case was filed last year in Turkey involving the alleged intimidation and beating of union activists at a Coke bottling plant.

The company denies wrong-doing in both cases but the allegations, together with claims of environmental abuses in India, have fuelled a student boycott against Coke in the US and Europe. New York University and Rutgers in New Jersey are among several campuses where Coke products have been banned.

The suit comes at an awkward time, when Coke is seeking to improve its image by rebutting allegations of wrongdoing more strongly and trumpeting initiatives to make it a better corporate citizen. In March, the company signed up to the United Nations Global Compact, a voluntary code of conduct for international businesses, designed to promote human rights, protect the environment and tackle corruption. "This is a natural evolution of our company's long-held commitment to responsible corporate citizenship," said Neville Isdell, Coke's chief executive.

The Maqsudi story is one the company would rather went away. The son of a wealthy Afghan family of Uzbek descent, Mr Maqsudi is a naturalised US citizen. The family had business and political connections in Uzbekistan, cemented by his 1991 marriage to Ms Karimova, and he was a logical partner for Coca-Cola as it eyed markets in the former Soviet Union.

But in August 2001, it all went badly awry after the marriage disintegrated and Ms Karimova returned to Uzbekistan from the US with the couple's two children. In a telephone interview Mr Maqsudi said that, despite winning a custody order from courts in New Jersey, where he lives, he has not seen his children again.

The arbitration claim alleges that following the separation "Ms Karimova and her father directed the full power of the government of the Republic of Uzbekistan at destroying Mr Maqsudi's investment in Uzbekistan", particularly his majority stake in the Coke bottling operation. Within 10 months of the relationship breaking up, the Uzbek courts confiscated Mr Maqsudi's share in the plant, to liquidate debts allegedly owed by Roz Trading, his Cayman Islands company that held 55 per cent of the bottling operation. Much of that stake would later end up in the hands of companies with close ties to Ms Karimova, who has built a business empire since her return.

Coke endured an 18-month shutdown of the plant that ended only last year but, despite attempts by the Uzbek government to gain control of its share as well, the company has managed to retain its stake in the operation. The filing alleges that, rather than coming to the aid of its joint-venture partner, the company collaborated with the Uzbek government and discouraged US authorities from intervening on Mr Maqsudi's behalf.

"Coke made a corporate decision that they were going to save their interests in Uzbekistan," says Stuart Newberger of Crowell & Moring, the lead lawyer on the case. Allan Gerson, a Washington lawyer who led the first suit against Libya on behalf of victims of the Lockerbie bombing and is also counsel on the case, says the company should have helped Mr Maqsudi. "Coca-Cola fully understood this was vengeance," he adds.

Coca-Cola denies those charges and says in a statement that "there was no collaboration and we are confident this will be upheld in any court or arbitration proceedings". Throughout the dispute, Coca-Cola Export Corporation, its export arm, has been a minority shareholder and "is not responsible for the dispute between Roz Trading and the government of Uzbekistan".

The Uzbek government, the third shareholder in the plant, is also named as a party to the arbitration claim. It did not respond to calls to its embassy in Washington. In a response last month to notification that a claim might be filed at the Vienna tribunal, the Uzbek government told Mr Maqsudi's lawyers: "Your statement that your client's participation in management was effectively impeded and also that any actions against your client have been performed illegally was a surprise for us."

Mr. Karimov, a former Communist party boss, has ruled Uzbekistan since 1991. Human Rights Watch has called the regime's record "disastrous", citing torture and crackdowns on human rights groups.

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the US government overlooked that record because Mr Karimov was seen as an important ally. He allowed the US to use an air base in the country as a staging ground for the war in Afghanistan. But relations have deteriorated since the government suppressed an uprising in the town of Anizhan last year, killing hundreds. Mr Karimov recently banned many western non-governmental organisations and expelled some US troops.

Coke says in its statement that it has "a strict Code of Business Conduct that is applicable everywhere we do business", adding that it "adheres to the local laws and regulations of each country as well as applicable US laws".

The case alleges that the company, while it may have obeyed local laws, violated its joint-venture obligations to Mr Maqsudi in order to protect its investment. Mr Newberger says he believes the decision was made at the highest levels of Coke's management in Atlanta.

A 2004 US Supreme Court decision in a case involving Intel opened the door to plaintiffs demanding documents from the headquarters of American companies for cases involving foreign proceedings. Mr Maqsudi's lawyers may thus be able to get their hands on minutes of directors' meetings and other internal correspondence to try to demonstrate Coke's complicity.

One key to making that case will be an exchange of letters in September 2001, which appears to show that top management and directors at Coke were well aware of the dispute. Farid Maqsudi, Mansur's older brother and partner in Roz Trading, wrote to Douglas Daft, then Coke's chairman and chief executive, following a raid on the plant that came just days after Ms Karimova returned home.

The letter said that agents of the Uzbekistan government "systematically detained, harassed, interrogated and terrorised the management and employees" at the Coke bottling operation. Nick Evangelopolous, the plant's general manager at the time, was held for 24 hours by the police and later said he had fled the country in fear of his life.

In the letter to Mr Daft, Farid Maqsudi pleaded for the company to weigh in against the abuses, saying that "for the Coca-Cola company to sit by and permit these police-state tactics to victimise the employees of CCBU, let alone collaborate with the perpetrators, is to betray the business principles that have made Coca-Cola one of the world's most respected brands".

Two weeks later, Mr Daft wrote back expressing regret and saying that the Maqsudis' personal turmoil was "undoubtedly disheartening...However, I believe it is conducive to our long-term business interests to separate the issues". In a later letter, the company called the dispute "a family matter in which we are not involved and do not wish to become involved". The Maqsudis' efforts to enlist Coke directors of the time, such as Warren Buffett, were similarly rebuffed.

Much of the case could turn on events shortly after the August 2001 raid on the plant. The suit includes a letter that appears to show that Coke, instead of challenging the raid and questioning the legitimacy of the tax audit, told the US embassy in Tashkent that the audit was legitimate. That reassurance helped to keep the US government from intervening at a time when, Mr Maqsudi says, pressure on the Karimov government might have been effective.

Coke is likely to argue that it was caught in the middle of a dispute between the Maqsudis and the Uzbek government. Like many of Coke's bottling plants around the world, the Tashkent plant bought concentrate from Coca-Cola but largely managed its own affairs. The company also points out that it, too, suffered significant losses because of the shutdown of the bottling facility.

Sonya Soutus, vice-president of Coca-Cola International, says the group's reputation is being sullied by an affair over which it had little control. "Taking into account the difficulty of our situation, there is quite a bit of evidence that proves we did everything we possibly could in the best interests of our stakeholders and the business in Uzbekistan."

Yet whatever its outcome, as Coke seeks to present itself globally as a good corporate citizen, the dispute is likely to serve as a reminder to it and other multinationals of the perils of doing business with autocrats.

Additional reporting by Andrew Ward

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.